During the 2020 U.S. Presidential Elections, platforms such as Facebook and Twitter flagged fake news through fact-checking. But despite these efforts, the U.S. Capitol was attacked, owing to widespread belief in false propaganda and misinformation. India has lessons to learn from this experience.

Information is power. Yet, unfortunately, the information we receive is heavily distorted due to misinformation and disinformation – accelerated by social media platforms. A survey report by the Reuters Institute at Oxford University suggests that almost 28 percent of Indian respondents consume news through social media, with 39 percent expressing trust in the information they read on social media (higher than in many countries). This data is concerning, primarily when civilians use social media for information during elections, as fake information can distort their choices.

Tamil Nadu is now gearing up for the 2021 Legislative Assembly Elections, expected to be held in May, although yet to be scheduled. But conspiracy theories and other fictitious statements are already spreading rapidly on social media platforms. For instance, recently, there was a Twitter trend titled #whokilledjayalalitha, which carried misinformation and disinformation. Further, Jayalalithaa’s close political aide, Sasikala Natarajan, was exalted on social media (along with disinformation and misinformation) as she returned to Chennai after serving four years in prison.

While quick and easy access to information is useful, lack of understanding about the accuracy of the information on social media is problematic – especially during elections – given that disinformation and misinformation spread faster than the truth.

But let’s first understand the difference between ‘disinformation’ and ‘misinformation’. When a person produces baseless and misleading information to deceive their followers, it is called ‘disinformation’. When their unsuspecting followers start sharing the same misleading information within their own network, it is called ‘misinformation’. In the case of the latter, the intention is not to deceive; instead, the reader believes that the information they read is the truth – confirming their pre-existing biases. Thus, disinformation starts a chain reaction of misinformation, which becomes a wild forest fire.

Regulatory Measures

During the 2019 Lok Sabha Elections, the Internet and Mobile Association of India (IAMAI) produced a Voluntary Code of Ethics for social media platforms. This voluntary code ensured that the platforms gave due diligence to the Election Commission (EC). In September 2019, EC announced that it would observe the IAMAI Voluntary Code of Ethics during all general elections.

While the code is a step in the right direction, it still doesn’t have any provisions for tackling disinformation and misinformation. In addition, the Intermediaries Guidelines (Amendment) Rules, 2018, which brings social media under its ambit, also doesn’t have provisions for tackling disinformation and misinformation in general.

Section 3(2)(f) of the rules comes close to addressing disinformation and misinformation, stating that the user agreement should inform users not to host or share information that “deceives or misleads the addressee about the origin of such messages or communicates any information which is grossly offensive or menacing in nature”. Yet, the section still needs clarity regarding framing and definitions and should move beyond the origin and tone and talk about the integrity of the message itself.

While the reframing of the Intermediaries Guidelines (Amendment) Rules can be a long-term solution, there is a need to immediately amend the IAMAI Voluntary Code of Ethics to include a section on disinformation and misinformation, with elections coming up in Tamil Nadu and other states. The section on disinformation and misinformation should be divided into two parts: 1) identifying disinformation and misinformation and 2) controlling the spread of the same.

Identifying Disinformation and Misinformation

This part of the code should oblige social media platforms to recruit more local fact-checking news organisations to check the accuracy of the information shared on the platform and flag/label it.

During the 2020 U.S. Presidential Elections, platforms such as Facebook and Twitter flagged disinformation and misinformation through fact-checking. This information related to allegations against election integrity, the premature declaration of results etc.

While it is important to flag such false claims on the election (commonly termed as ‘election-related information’), restricting the flagging practice only to such information is not fruitful. The ambit of ‘election-related information’ has to be expanded under the IAMAI Voluntary Code of Ethics. The term should include all kinds of information, include hate speech, hyper-partisan rhetoric, information based on caste, gender and religion, and so on.

In 2017, the Supreme Court restricted the use of caste and religion-based information in election campaigns. But representatives of political parties, politicians and others could use the caste and religion-based information as part of the election campaign in various contexts – for instance, to demonstrate caste-based oppression. This can be innocuous in nature, but false information on caste and religion (used intentionally/unintentionally) misleads voters and starts a chain reaction of misinformation. Thus, not repeating the same mistake, the code has to insist on case-by-case fact-checking of information, instead of a bracket restriction on a specific type of information in general.

Controlling the Spread of Disinformation and Misinformation

Despite efforts to flag fake news, the U.S. Capitol was attacked on 6 January 2021, thereby proving the need to control the spread of disinformation and misinformation more effectively. Following the attack, social media platforms blocked the then U.S. President Donald Trump, but more should have been done before the damage occurred.

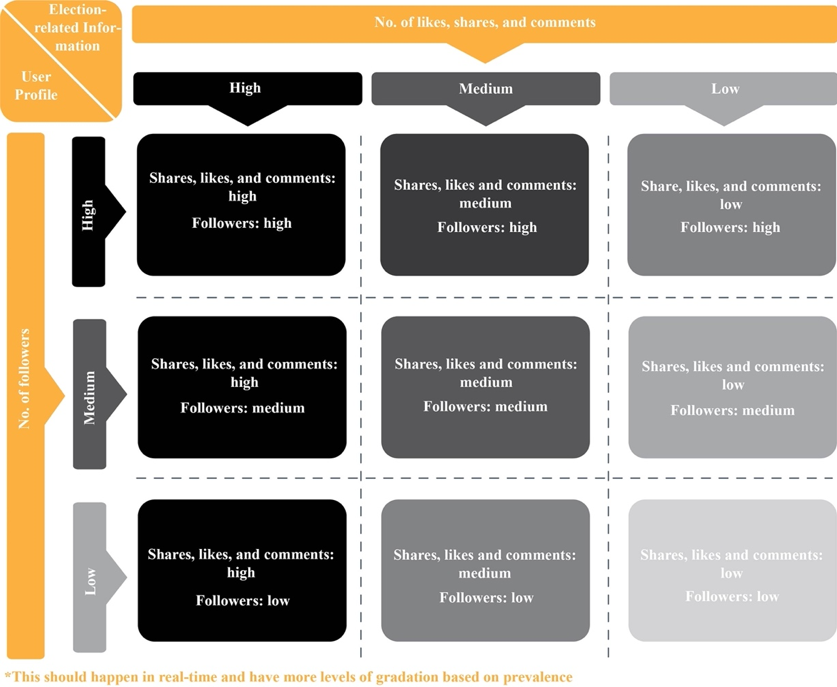

To prevent the spread of fake information, the code should mandate a prevalence-based gradation process (illustrated below) of ‘election-related information’. The platforms can use a gradation matrix to formulate various ex-ante measures to tackle the spread (ex-ante means acting before an event, based on a forecast, whereas ex-post means reacting after an event has occurred).

The prevalence-based gradation process should not cost platforms much, since they already capture data related to prevalence and reach. Further, since the same information flows through multiple platforms simultaneously, the Voluntary Code of Ethics should also ensure uniformity in implementing these provisions, whereby every member platform must take almost similar actions against misinformation and disinformation.

However, excessive regulations could hamper the negative liberty that social media platforms enjoy. Social media platforms still enjoy a safe harbour under Section 79 of the Information Technology Act, 2000, which exempts them from liability for the third-party content they host under certain circumstances.

Utilising the gradation matrix of prevalence-based analysis (as illustrated above), the ex-ante standards for ‘election-related information’ should be scaled. Since ‘election-related information’ posted by a highly followed user gets greater traction, it should be subjected to higher scrutiny.

Building More Responsible Social Media Platforms

In addition, the ex-ante standards should also include provisions on the appropriate use of algorithms by social media platforms to recommend election-related information to each user. This is important because our biases are reinforced by these algorithm-driven recommendations and keep us away from content that does not fit our ideology. This information ‘filter bubble‘ could block counter-arguments from reaching us, including fact-checks.

Further, the ex-ante standards and other policy measures for ‘election-related information’ can be enhanced and audited by incorporating feedback from users. The feedback can be derived by aggregating grievances to find patterns. For instance, Facebook reinstated the award-winning image of a naked girl fleeing napalm bombs during the Vietnam War after receiving negative feedback following its takedown.

While Facebook received this feedback through newspapers and civic movements, it still shows that aggregating grievances can provide feedback on policies and actions. Setting up a robust grievance redressal mechanism could be a better way to receive feedback and can also be used for settling disputes.

Moving a step further, it is also important to feature regional (state-wise) differences in terms of language and culture into grievance redressal mechanisms. Therefore, platforms must have a regional grievance office (in Tamil Nadu for the upcoming elections, for instance) to handle election-related information grievances.

But any measures taken by social media platforms are bound to raise concerns regarding their control over public speech and information. For instance, while the ban on Trump by social media platforms was widely seen as a positive move, it also reveals the power that social media platforms wield. Thus, to check and counterbalance this power, there is a need to establish a body like the Social Media Commission at various levels (international, country-level, district or state-level) as an arbitrator for disputes (with provision to appeal in a court of law).

These regulatory measures are not mutually exclusive and will need to work in synergy to tackle disinformation and misinformation. But it’s time to put the genie back in the bottle.

Kamesh Shekar is a tech policy enthusiast. He is currently pursuing PGP in Public Policy from the Takshashila Institution. His views are personal and do not represent any organisations.