The burden of upholding democracy rests on three pillars: government, institutions and civil society. In India, while the former two have received attention from researchers and the media, the third pillar is scantily discussed. In recent years, civil society organisations have increasingly come under attack.

The constitution of India, home to 17 percent of the world’s population, declares that India is a “sovereign, socialist, secular, democratic republic” and all its citizens are guaranteed liberty of thought, expression, belief, faith and worship.

Notwithstanding this statute, reports on the decline of India’s democracy have gained momentum in the past few months. The two reports that have contributed to this narrative are from Freedom House and the V-Dem Institute. Both these reports suggest a decline in India’s democracy and the establishment of an electoral autocracy. The COVID-19 pandemic seems to have added to this decline, with several restrictions on the freedom to mobilise or protest against government policies, according to the V-Dem report.

Owing to its size and also the fact that it is the only lower-middle-income country that has had competitive multi-party democracy since its independence (except for two years in the mid-1970s), India is of paramount importance for discussions on the quality of democracy. Researchers have pinned down the burden of upholding democracy on three pillars: government, institutions and civil society. While the former two have received attention from researchers and the media, the third pillar is scantily discussed.

By the World Bank’s definition, civil society organisations (CSOs) include a wide range of organisations: community groups, non-governmental organisations (NGOs), labour unions, indigenous groups, charitable organisations, faith-based organisations, professional associations, and foundations. They typically have a presence in public life and express the interests and values of their members and others, based on ethical, cultural, political, scientific, religious or philanthropic considerations.

Conceptually, however, ‘civil society’ proves to be diffuse, hard to define, empirically imprecise, and ideologically laden. In India, civil society’s composition, roles, relationships and even resource bases are undergoing vivid alterations under changing societal circumstances.

Changing Civil Society Landscape in India

For the sake of simplicity and a better understanding of the role of CSOs in India, three time periods can be marked.

First, during the decades prior to economic liberalisation (1990-1991), CSOs worked for the overall development of society, focusing mainly on uplifting the downtrodden. After that, in the 1990s and the ensuing two decades, CSOs started actively collaborating with international organisations (like the UN and the World Bank) mostly aiding causes of development and governance. Finally, from 2010 onwards, the CSOs experienced increased politicisation (Jan Lokpal and anti-corruption movements).

Therefore, in recent times, the policy advocacy role of CSOs cannot be ignored. For example, significant acts like the Right to Information Act (2005) and the Domestic Violence Act (2005) have been passed with extensive CSO support.

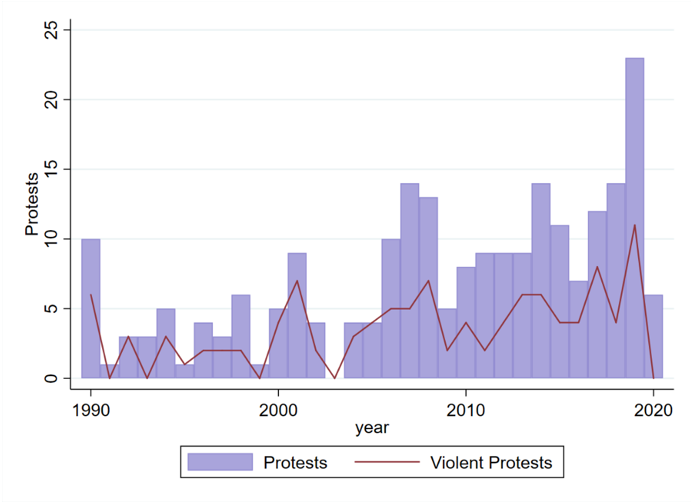

Nevertheless, along with their traditional roles, certain changes in the composition and roles of CSOs have been noticeable over the last two decades. As a recent illustration, the 2020-2021 farmers’ protests in opposition to the three farm bills passed in 2020 have turned into a pan-India movement.

Yet, experts warn that India is following the typical pattern for countries that saw a gradual deterioration in democracy metrics, with freedom of media, academia and civil society being curtailed to a large extent.

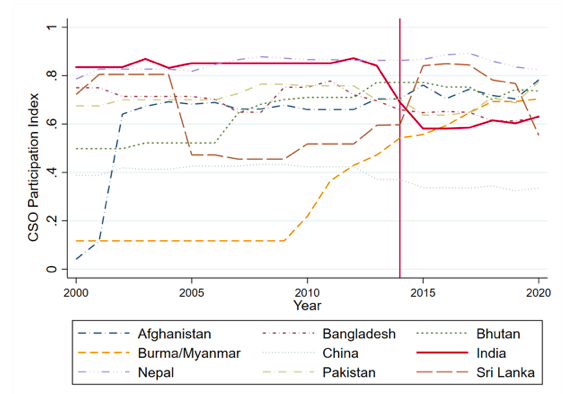

The CSO participation index is built in response to the following questions: Do policymakers routinely consult prominent CSOs? How large is the involvement of people in CSOs? Are women prevented from participating? And is legislative candidate nomination within political parties highly decentralised or made through party primaries?

Designed to provide a measure of a robust civil society – one that enjoys autonomy from the state and in which citizens freely and actively pursue their political and civic goals – the CSO participation index plot in Figure 2 highlights a problem afflicting Indian society. From Figure 2, we can see that India’s CSO participation has deteriorated, with a steep drop during the 2011-2016 period (noteworthy is that its neighbours saw a rise in CSO participation during this period).

A case in point is the increased use of the Unlawful Activities Prevention Act (introduced 1967 and latest amendment in 2019) and the Foreign Contribution Regulation Act (introduced 2010 and latest amendment in 2020) to restrict foreign funding for NGOs. Also, sedition cases against CSO actors have been on the rise, with a 28 percent increase between 2014 and 2020 when compared to the yearly average in 2010-2014.

Pattern of Autocratisation

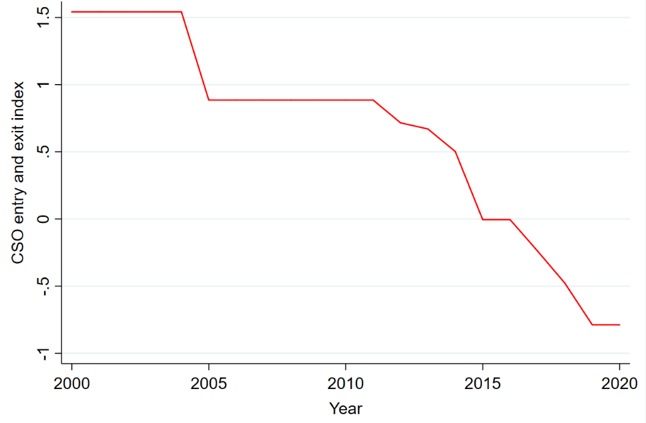

The V-DEM institute asked respondents: “To what extent does the government achieve control over entry and exit by civil society organizations (CSOs) into public life?” India’s performance has progressively fallen on this metric (Figure 3). What this means is that as opposed to unconstrained or minimal control in the early 2000s, the entry and exit of CSOs in public life has been moderately or substantially controlled in recent years (a lower number on this index indicates that the government uses political criteria to bar organisations that are likely to oppose it).

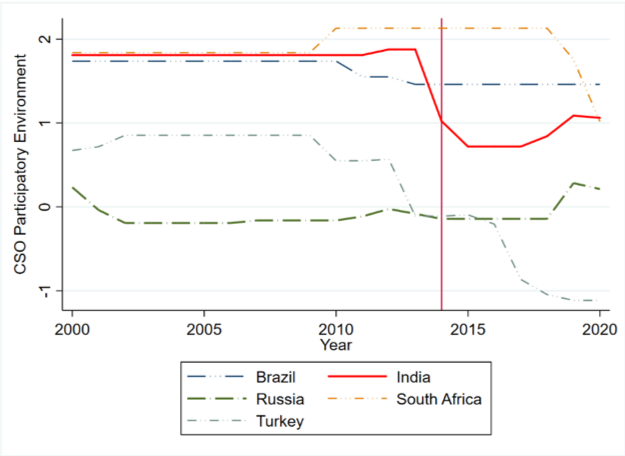

What is noteworthy is that India is joined by several G20 nations, such as Brazil, South Africa, Turkey and Russia, in the decline of democratic values. This is evident from another CSO-related metric: the CSO participatory environment, which captures the involvement of ordinary citizens in CSOs. The declining numbers indicate that many associations are state-sponsored, and although a large number of people may be active in them, their participation is not purely voluntary.

The commonalities between these countries with respect to autocratisation are palpable. The first step towards autocratisation is the restriction and control of the media, clubbed with the curbing of civil society and academia. On the sidelines is the fanning of polarisation and religious hyphenation.

With the empirical evidence presented above, it is clear that the civil society discourse in India highlights afflictions in the religious freedom and human rights practices prevalent in Indian society. In today’s India, these seem to be conditional on the interplay of the political and legal spheres, which is underlined by a strong air of division and polarisation.

However, the pro-democracy protests in countries like Myanmar, Belarus and even the U.S. suggest that forceful state restrictions cannot dissuade pro-democracy forces. CSOs in those countries have found several alternative ways to draw attention to their causes (social media being one of them). It is important that the role of civil society as the third pillar of democracy in India is widely discussed, especially in view of these declining metrics.