The Summit for Democracy was a product of complex U.S. realpolitik – one which seems to have conflated the goals of subduing China and espousing democracy. But if America truly wants to contain Chinese influence, couching its foreign policy in terms of democracy will prove counterproductive.

Ever since the U.S. announced a Summit for Democracy and subsequently the list of invited (and uninvited) countries, rhetoric around democracy has dominated global discourse.

Now that the Summit has been done and dusted, it is only natural to try and make sense of the rationale underlying it. What exactly was this ‘Summit for Democracy’? Is the world at a stage where democracy needs to be defended? A decade ago, any talk of needing to defend democracy would have been inexplicable. Yet, here we are: a world thriving on the rails of globalisation is also unfortunately a world decadently sliding towards authoritarian proclivities — the threat of foreign agents interfering in elections, online disinformation, political polarisation, and the temptation of populist alternatives just scratches the surface.

The democratic recession is, indeed, deepening. According to a recent report by the International Institute for Democracy and Electoral Assistance (IDEA), the number of backsliding democracies has doubled in the past decade, now accounting for a quarter of the world’s population. This includes established democracies such as the United States, but also member states of the European Union such as Hungary, Poland and Slovenia. More than two-thirds of the world’s population now lives in backsliding democracies or autocratic regimes, not to mention the increase in the number of countries downgraded by the more polemical Freedom House from ‘free’ to ‘partly free’.

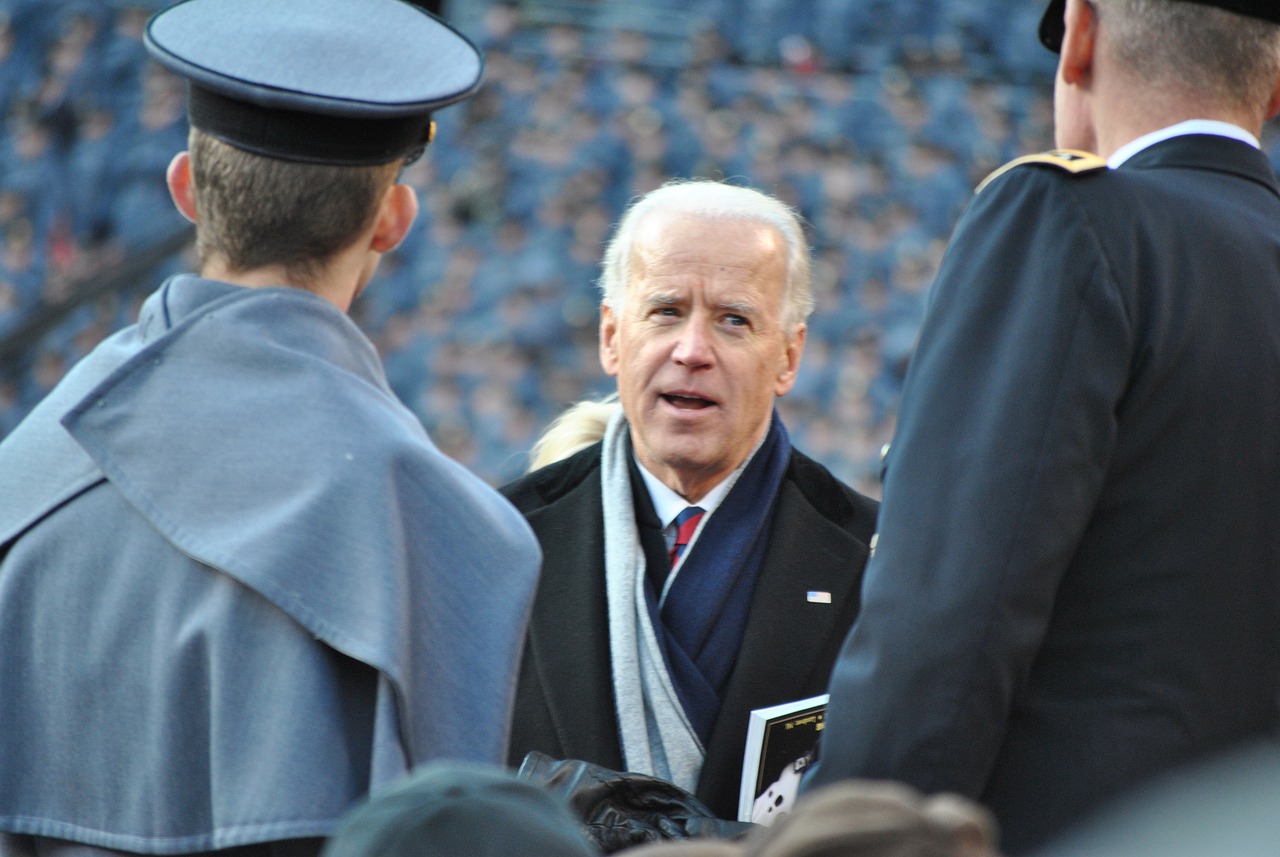

But given the cold calculus of international politics, the Summit was far from a mere ‘Summit for Democracy’. “We have to prove democracy still works”, U.S. president Joe Biden explicitly pronounced, even before the Summit itself. The implication is obviously to arrest the worsening worldwide autocratic trend, aside from a thinly veiled attack on America’s primary geopolitical rival: China. The invitation list was more geopolitical than anything else, with the usual suspects (Russia and China) not making the invitation list. But the primary indication of the China factor was the invitation to Taiwan, especially given that only a handful of nations – the U.S. not among them – recognise it as sovereign.

We must hence view the Summit as a product of complex U.S. realpolitik – one which seems to have conflated the goals of subduing its foremost political rival and espousing democracy as an ideal.

The U.S. is the jack of both trades and the master of none in this case, so this doesn’t seem to be a particularly sagacious tactic. Besides providing China with fertile ground to attack the Summit as politically motivated (China has previously been known to criticize U.S. plurilateral platforms as “exclusive multilateralism”), this ploy also ends up reducing the U.S. commitment to democracy to mere tokenism. Therefore, this conflation in the long term is problematic, to say the least.

Beijing’s announcement of a white paper just a week before the Summit was an intriguing (if not wholly unsurprising) development in this regard. An example of classic Chinese propaganda, it unabashedly glorified the virtues of what it called “Chinese-style democracy”.

While the world knows better than to take Beijing at face value, Washington should be wiser than to ignore the message. These aren’t the 1980s; since China’s economic base is well-covered, it isn’t hampered by the criticism that the Soviet command economy had elicited. The Chinese are shrewd; they know their people well and realise their willingness to surrender rights in favour of prosperity. They’ve provided their people with what they desire the most: stability. Why give this away for a democratic future?

Elusive dreams of a democratic future hence don’t impinge on Beijing’s conscience. As Vijay Gokhale has pointed out in his book, Tiananmen Square, “There are still those who dream of a democratic China, but most of them emigrate to the West and are irrelevant to the Chinese.”

The white paper’s nudge to “Western-style democracy” is clear: The U.S., with its own house reeling from the bitter after-effects of Trumpism, can’t claim to be Reagan’s “shining city on a hill” anymore (especially after the Hill was desecrated earlier this year).

In that sense, perhaps the Summit isn’t as much about re-affirming the legitimacy of democracy, but more about restoring the credibility of a nation past its unipolar moment. Were Washington indeed serious about standing up for democracy, the list of invitees would have been much more inclusive. Mohamed Zeeshan has lucidly pointed out how the tight-handedness of the U.S. in this regard could actually be anathema to its strategic ambitions in the Indo-Pacific.

There is another more encompassing aspect that Washington seems to have been impervious to: The buzzword of democracy doesn’t suit many of its own allies either. Consider Vietnam, for instance. It has been growing friendlier with the U.S. over the years and has turned out to be a useful economic partner, besides a natural ally in the effort to constrain Chinese ambitions in the South China Sea. Any effort at economic decoupling with China would have to include increased reliance on partners like Vietnam. But Vietnam continues to be a Communist Party-dominated autocracy – creating a strategic inconvenience that might come to haunt the U.S. later.

The American instinct to couch all foreign policy in terms of democracy is therefore counter-productive. There are just too many intricate loose ends. Even if we view the Democracy Summit purely as a ploy to make China uncomfortable, the irreconcilable Russian factor looms large. Russia-U.S. interests can never be totally aligned, but finding a mutual convergence would suit both. The U.S. knows that Russian president Vladimir Putin won’t improve his record on human rights, but he could at least be convinced to accept international norms in cyberspace – a much more pragmatic and plausible bargain. In return, a Russia knee-deep in Western sanctions could use U.S. assistance.

In fact, some saw Biden’s early outreach to former German chancellor Angela Merkel and French president Emmanuel Macron as an attempt at stitching a rapprochement with Putin. The logic was certainly there; as economist Melvyn Krauss had then written: “Putin recognises that his country has received scant benefits from his relationship with Xi’s China… By bringing Russia in from the cold in which the West has placed his economy, Putin could also reverse its descent into economic sclerosis and stagnation.”

An “alliance of democracies” sounds nice, but the moment America defines its foreign policy in such terms, a deal with Russia becomes nigh to impossible – especially now with the Ukrainian question further complicating matters.

What then is the key to this impasse? Is the lesson of the attempted Summit for Democracy that U.S. foreign policy must now be divorced from democracy in order to pursue the broader ambition of restraining China?

Mathew Yglesias hits the nail on the head in Bloomberg as he reconciles these two seemingly incompatible factors: “Being realistic about America’s real aims does not require abandoning democracy as a value, or denying that it has a role in U.S. foreign policy. But duplicity has a role in diplomacy… The goal should be to exploit tensions that exist between authoritarian regimes — tensions that are clearly present in the Russia-China relationship. Ideological rigidity will only succeed in uniting these regimes against the U.S.”

The Summit for Democracy (albeit underwhelming as it was) has set the world order up for a delicate game. The U.S. faces the imperative of anchoring a stable balance of power against China while also staying true to its democratic convictions. With the world more multipolar than it has ever been since World War II, the future of many hangs in the balance.

Armaan Mathur is pursuing Political Science Honours at Kirori Mal College, Delhi University. He has previously written for the Student Edition of the Hindustan Times and is passionate about history, political science, literature and international relations.