Unlike the U.S., which was criticised for hoarding vaccines with no clear intention to use them all, India was the poster boy of true global integration – sharing its already limited resources with the ones that needed it. But amidst the pride and triumphalism, the Indian government forgot to plan and prepare.

On 17 March 2021, Freedom Gazette published my empirical analysis on India’s ‘Vaccine Maitri’ – vaccine exports to other countries as grants under the World Health Organization’s (WHO) COVAX programme and as commercial contracts.

We were basking in the glory of our ‘developing’ country becoming the saviour of the world, thanks to its impressive vaccine production capacity. My inbox and social media profiles were flooded with congratulatory messages from friends abroad and within India. To validate our short-lived success, ministers – Indian and foreign – tweeted gratitude messages with an animated banality. Nevertheless, as an Indian, I could not have been prouder.

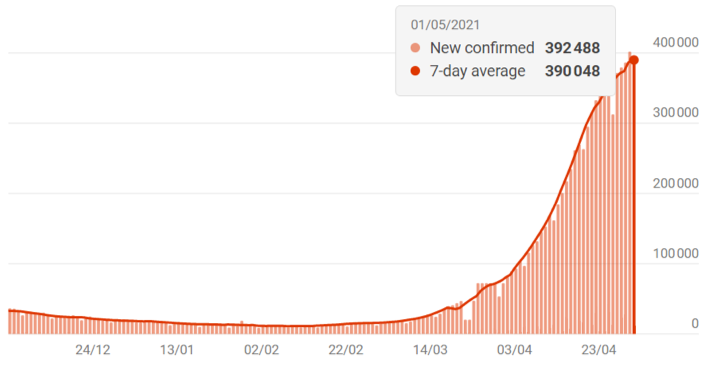

At the same time, a disaster was unfolding in the same country, with daily new infections breaching the 100,000-mark on 4 April. The daily death toll breached the 1,000-mark ten days later and is now well over 3,000.

To add fuel to the fire, chronic under-preparedness on the part of the government has exposed our over-stressed medical infrastructure. Visuals of people begging for oxygen and incidences of medical fraud have dominated the headlines for the past month.

Could we have predicted this collapse? Yes. Could we have avoided it? Yes, again. Did this happen because we exported our vaccines? Maybe yes, maybe no.

To take an objective look into what transpired in the past six weeks, let us look at some data. It is important to iterate that this is not an opinion piece.

The Slow Death of India’s Vaccine Diplomacy

On 5 May, the tally of vaccines supplied under Vaccine Maitri stood at 66.4 million doses (10.7 million doses as grants, 35.8 million as commercial supplies and 19.8 million under COVAX). India’s vaccine exports commenced one week after it started inoculating its own population on 15 January 2021.

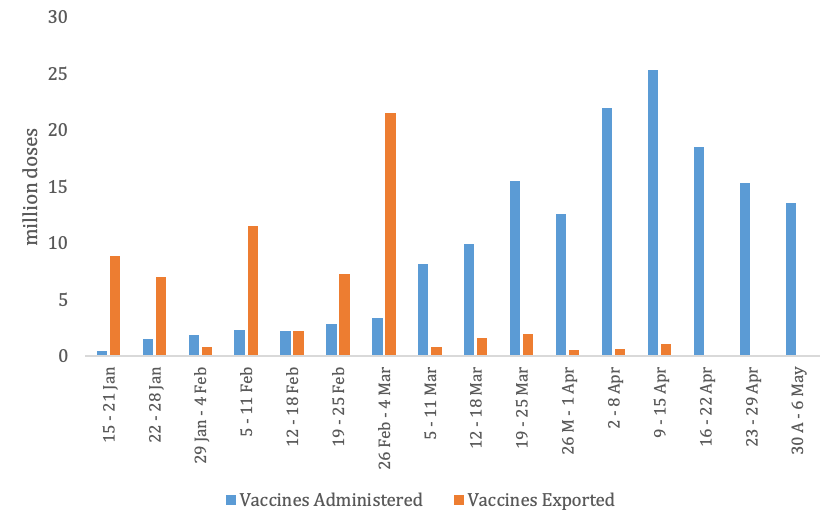

In the initial six weeks (until 5 March), India was exporting more vaccines than it was administering internally (see Figure 1). Subsequently, there was a change of tack, with the following weeks seeing a continuous drop in vaccine exports. The last batch of made-in-India vaccines was exported on 22 April, which means that, for over two weeks, India has not exported a single dose to other countries.

Compare this with India’s internal vaccination numbers. As of 4 May, 160.5 million Indians (12 percent of the total population) have received at least one dose of the vaccine (19 percent of these, i.e. 30 million, have received both doses). The vaccine doses exported by India (66.4 million) are 41 percent of the doses administered in India, with the bulk of these having been sent out in February.

Globally, as of 2 May, the United States has vaccinated a similar number of people: 146.2 million (44 percent of its population) have received at least one dose of the vaccine. Meanwhile, in Germany, this number is 25.5 million (28 percent of the population), and in France, it is 19.65 million (26.5 percent of the population).

The U.S. made its first commitment to export vaccines only on 18 March, about two months after India had already supplied vaccines to its neighbours. At the same time, the EU faced considerable backlash, with its vaccine exports outnumbering the vaccines administered to its own people.

While the UN, WHO and the Gavi Alliance emphasised the perils of vaccine nationalism, India seemed to be the one country that was overcoming the ‘inescapable trilemma’ – that democracy, national sovereignty and global economic integration are mutually incompatible. Unlike the U.S., which was criticised for hoarding vaccines with no clear intention to use them all, India was the poster boy of true global integration – sharing its already limited resources with the ones that needed it.

Did India Export Too Many Vaccines?

India’s vaccine diplomacy and domestic vaccination campaign had their hearts in the right place. But they were severely hurt by the exponential surge in cases through April (see Figure 2). The second wave was always in the offing. But it was accelerated by continuous and crowded electioneering, uninhibited religious congregations, mass gatherings, and a general complacency shared by the leadership and the citizens.

The pertinent question remains: Could we have done better if we had not exported 66 million vaccine doses to other countries? We must objectively review the following to come up with an answer:

First, in case we had not exported them, did we have the capacity to administer these 66 million doses to our own people?

Our vaccine administration has ramped up slowly and steadily since it began on 15 January. The two major manufacturers with approvals (Serum Institute and Bharat Biotech) have a combined capacity of 75 million doses per month. The advance money sought by these companies from the government to ramp up production has come in late and has also been girdled with controversy.

Statements put out in the public domain by the promoter of Serum Institute, Adar Poonawala, show the extent of pressure these companies have been subject to. The need of the hour is to support the existing approved manufacturers and also involve other large pharmaceutical companies, whose capacities can be put to best use in this critical hour.

Second, could we have ramped up capacity to only export what was extra?

To answer this, we must ask again what we define as ‘extra’. When India seemed to have won the battle of the first wave, this ‘extra’ did indeed seem available for exports to leverage our international position.

In hindsight, it seems that our government and allied machinery, as well as the people at large, did not pay heed to warning signs raised by several researchers, doctors as well as the Parliamentary Standing Committee on Health and Family Welfare. A report submitted by the parliamentary panel in November 2020 warned of “a possible second wave of Corona especially in the ensuing winter season and superspreading series of festive events”.

Regardless, did the government have a daily, weekly or monthly plan of vaccine administration? It seems the answer is no. And even if it did, it is not public.

It is no secret that the red flags raised by experts and committees were ignored, and in the current situation, even a single dose of vaccine sent abroad (or wasted) seems to be a bad idea. Yet, it is important to point out that developed nations like the U.S. and Germany have been called out, by their citizens and the international community, for hoarding and wasting vaccines in large numbers.

Third, do our foreign policy commitments allow us to practice vaccine nationalism and vaccinate only our own citizens first?

India is the vaccine capital of the world. However, for many vaccines – especially the COVID-19 vaccine – we rely on raw material from other countries. The Serum Institute’s Covishield was developed in the UK and falls under a $750 million agreement, with the Coalition for Epidemic Preparedness Innovations (CEPI) and the Gavi Alliance, to supply one billion doses for low-and-middle-income countries. Therefore, India cannot refuse vaccine exports or go back on its commercial commitments, if it projects itself as a reliable and affordable supplier in the global pharmaceutical value chain.

Nevertheless, we can now see that the virus outperformed the government’s short-sighted plans. Just after the kick-off of India’s internal vaccine drive, The Print reported that Indian officials were getting ready to export 50 percent of the stocks that were then available as a ‘goodwill gesture’ – which, of course, went through.

Of course, these questions are not easy to answer. But that does not mean that they must not be asked.

In my piece on 17 March, I wrote: “India has been acting fast on its vaccine disbursal to foreign states under its vaccine diplomacy initiative. Critics have often questioned this in view of the large number of doses that India itself will need in the coming weeks to inoculate its own 1.3 billion people.”

In hindsight, I feel guilty of inadvertently predicting an impending disaster, fuelled by irresponsible behaviour on the part of our leaders. The virus snuck up on us while we were basking on past laurels and declaring victory even before touching the finish line.

Neha Bhardwaj Upadhayay is a researcher and instructor in economics at the University of Paris-East (unit Erudite). She works in areas of political economy, trade and gender. Her work is based on econometrics and data analysis.